Dedicated to exploring the connection between industrialization and architecture, this post starts from the very beginning. It is clear that the confluence between the two started in the USA at the beginning of the 18th century with the “balloon frame” concept. This was a revolutionary technique which started from strips of wood, and allowed entire façades, sometimes even entire buildings to be created in the factory before transporting them to the desired destination. Western movies are a good reflection of this form of construction, generally helping to colonize a country that is yet to be explored.

Nevertheless, the real involvement between the two did not begin to grow until the early 20th century when Henry Ford optimized Ransom Olds’ chain production to market the “Ford T.” Mass production meant a huge leap forward for the Industrial Revolution, enabling companies to offer quality standardized products at a reasonable cost for the working class. The Chain Production, the replacement, and the automation of tasks, now determined the industrial manufacturing industry as it tried to supply products to a society of millions.

After the First World War, new cultural movements and avant-garde schools like “Bauhaus” (1929) arose in Europe. Their goal was to integrate art and functionality through industrial processes, as well as establishing new standards and academic foundations for the next generation of industrial design. Lead by Walter Gropius, the “Staatliche Bauhaus” produced a great environment for the education and progress of modern artists, among which was Mies Van der Rohe, the father of architectural minimalism and author of the eternal phrase “less is more.”

At the same time, in June 1928 architects such as Le Corbusier and Sigfried Giedion funded the CIAM (International Modern Architecture Congress). The CIAM was a factory of ideas created to work on a movement considering the simplification of forms along with the absence of any ornament. Alongside this, it included a renounce of classic academic compositions which had been replaced by new modern art trends. (i.e, cubism, expressionism, neoplasticism, futurism…)

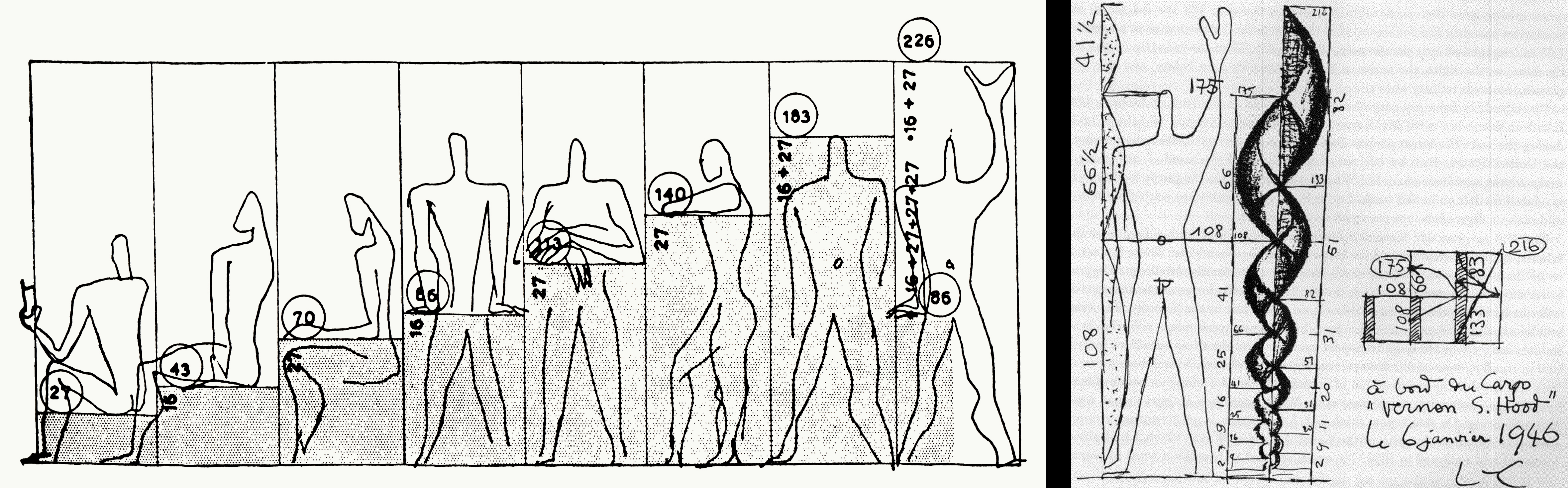

However, among all contributions of the CIAM, the implementation of new materials such as steel and reinforced concrete, combined with new manufacturing technologies is what made the real difference in architecture. Until the first half of the 20th century, modern architecture followed a trend that Ramón Araujo defined as “integral seriality”in his article “Assembly Lines.” It was Le Corbusier who defined the concept of a house as a “machine for living in,’ alongside implementing the design of complete building models to be produced consecutively. In order to get these consistent designs, Le Corbusier started with “Le Modulor,” a measuring system he developed to find a mathematic relation between the human being and nature. The goal of all this, was to use the module as the basis of his architectural plans. Therefore, his proposals were much more than a mere standardization of components.

The “Unité d’habitation” architectonic icon of the 20th century, is a clear example of the how buildings were standardized for their replication. This icon is an influential building (140 meters long, 24 meters width and 56 meters height), that contains 58 duplex apartments per level, only accessible through a big internal corridor located each three storeys. Based on reinforced concrete panels, the building was created in a way that allows great permeability on the surface, thus creating a communication space between interior and exterior. The roof was raised as one of the major social areas, including an athletic track of 300m, covered gym, nursery and much more. The first of these units to be constructed was CitéRadieuse (1945) while Nantes-Rezé (1952), Berlín (1956), Briey-en-Forêt (1957) and Firminy (1960) came afterwards.

References:

*Ramón Araujo. Cadenas de Montaje. Arquitectura Viva Nº 156